USC Upstate biology professor Kimberly Shorter, Ph.D., and her students spent the summer researching genetic material that one day may offer insight into a variety of diseases.

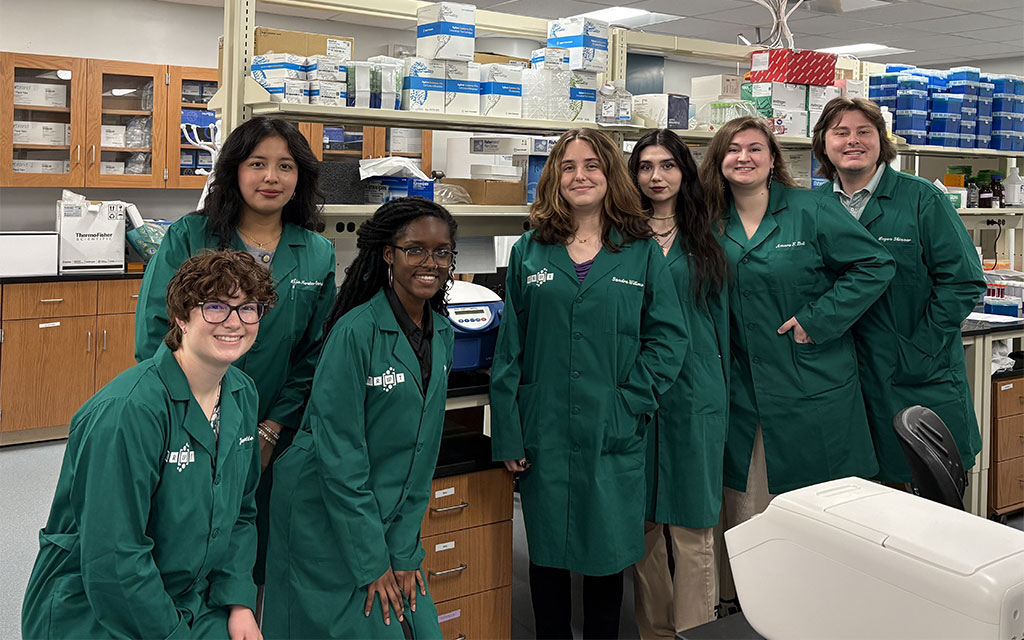

As part of a new NIH grant, Shorter has been studying the effects of a small, non-coding RNA on gene expression and epigenetic marks. Eight students joined the professor this summer on the research.

Shorter offers an analogy to describe her research. Though she did not originate it, she has used it to offer a clearer view of epigenetics, a field focusing on how human behavior affects gene expression.

Think of human genetics as hardware of a computer and epigenetics like the software—the latter informing genetics how to run. Epigenetic marks can be altered by daily activities, Shorter explains, such as eating or drinking or even stress. In turn, micro-RNA can change with environmental factors, inhibiting the process that naturally occurs with DNA as it codes for proteins. Protein aids in healthy cell function.

“These epigenetic marks on the DNA or on those proteins that the DNA has to tie itself around, and then even those non-coding RNAs floating around, those all are like software,” Shorter says.

“Our daily lives affect the software. It can program in good ways and in bad ways … everything we do and encounter every day is impacting that software.”

These impacts now are under a microscope, as Shorter and her students look at microRNA-718 (or miR-718) by running tests on cells cultivated in the lab. They’ve spent eight hours a weekday in the Smith building collaborating on the work.

Other students will join the team to continue the research in the fall.

“There’s not a lot known about this non-coding RNA,” Shorter says. “There’s a little bit of evidence that when it increases in expression, you get poor prognosis in cancer.

“One of the things we’re trying to do is understand what is this small RNA doing? What is it impacting? What is it actually targeting that’s making it so bad that cancers would have bad outcomes.”

Shorter says small RNAs like what she studies are “known to underpin many disease types” and, generally, “all epigenetic marks are now well-understood to be agents that cause a variety of diseases.”

They include various cancers, neurological ones (degenerative like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s), developmental like autism, and psychiatric like schizophrenia — and autoimmunity, according to Shorter.

“That’s our big question here is, what is it about this micro-RNA? What is it doing in your cell when it goes up that it would cause these things?” Shorter says, “and that’s what we’re trying to figure out because down the road, what that could eventually lead to is whether a medicine can treat for those diseases.”

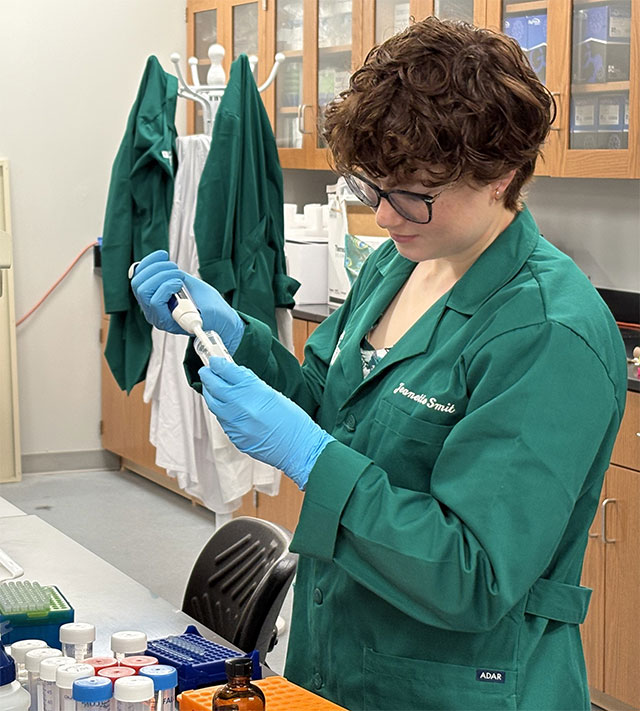

Student researcher Jeanette Smit, a rising senior and biology major, is one of the eight students who researched this summer.

She understands their work is a small part of a larger picture.

“We’re doing some very important, not only preliminary research but exploratory research into what miR-718 could be doing,” Smit says.

“It may seem small, like we’re only looking at one micro-RNA and there are like thousands in your cell, but we can only look at one so I’ve kind of realized that’s what each lab does.”

Smit, who also has a concentration in pre-med, describes it as a part of a larger pool of information to which many labs and researchers contribute.

She was drawn to the research topic based on her own experiences. Shorter’s research in neurobiology hits home as she has a family member with bipolar disorder. She also was diagnosed with leukemia at 16 and is now in remission.

“Her research was kind of the perfect fit,” she says.

She also leaned into research because of her major and her interest in becoming a doctor. The university’s pre-med program and acceptance rate into medical schools brought her to Spartanburg.

Fellow researcher and rising senior Amara Bolt came to Upstate for the nursing program but later changed her major to biology. When interviewing Shorter last summer, she said the professor explained her research in a way that was easy to grasp, and she also was interested in the neuromedical side of it.

Now in her second summer researching, Bolt has enjoyed the challenges and strides made — including being able to help mentor new student researchers.

She also hopes the work she and her peers are doing encourages other students to consider research for more reasons than fulfilling a requirement.

“It’s more than that, you know,” Bolt says. “I hope that they would want to join these programs, maybe not at our school, but others as well, and look for their curiosity to grow their scientific knowledge.

“Because being in science period, you’re always going to be learning. It’s a never-ending process and you might as well have fun while you’re doing it and learn something new.”

For Shorter, research became a route she pursued after originally thinking she would be a doctor. She joined the faculty at USC Upstate 10 years ago after finding an opportunity she felt would be perfect.

As a first-generation college student, Shorter says she often finds common ground with students who are new to the college experience. And she’s proud to see her work leading to a grant funded by the NIH.

“I hope that through seeing me accomplish this, my students all can know that it is possible.”